A public service announcement from your friends at Blue River Capital Management:

If someone is trying to sell you a whole life insurance policy, DO NOT BUY IT.

Thank you for attending our TED Talk.

That might be a little harsh, but it’s advice that would serve a lot of people well. We will tell you why, but let’s start with some basics.

Most commonly bought and paid for through annual premiums, life insurance comes in two basic forms, term and whole life. Term life insurance lasts a limited time, like 10/20/30 years or until a certain age. If the insured outlives the term of the policy, no death benefit is paid. Whole life insurance, like the name suggests, is designed to cover the insured’s whole life with a death benefit paid upon death (although many whole life policies have an age cap, often age 100).

Since term policies may not pay a death benefit, they are usually much cheaper than whole life policies whose death benefit is essentially a question of when, not if (we’ll expand on this later).

An obvious challenge we see in the life insurance industry is an inherent conflict of interest. Different companies and products may vary, but what we can glean is that sales commissions are often between 40% and 110% of the first-year premiums plus an annual residual payment for each year’s premium. NerdWallet estimates that 5% to 10% of all the premiums you pay could be commissions.[1] Unfortunately, we have seen many instances where investors have been convinced to buy more expensive and longer-lasting policies than we think is justified, and the sales rep is the only obvious winner.

Given that whole life policies are nearly guaranteed to make a payment but term insurance policies are not, our more cynical friends might view outliving a term life insurance policy as a doubled-edged sword: congrats on staying alive but say goodbye to the premiums you have paid.

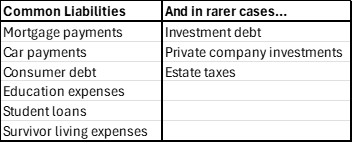

While we can understand this argument, it’s critical to remember what life insurance is for: life is uncertain and life insurance death benefits can cover known liabilities, which commonly are:

So, who should buy life insurance? A financial advisor (ideally one who does not also sell insurance products given the inherent conflict of interest) can help you figure out if it is appropriate for you and how much coverage you should have, but here are some factors that can make life insurance more valuable:

- Young children – Kids are expensive, and multiple kids usually translates to higher costs, especially if you want to plan for education expenses.

- Health issues – If you have a shortened life expectancy, you may have fewer years to work and save. Unfortunately, these same issues may make it harder or more expensive to get insured.

- Income dependence – Households that rely entirely or mainly on a single income have a larger risk.

- Debt-to-assets – A higher rate of debts (mortgages or other loans) relative to your asset base could exaggerate the risk of a loss of income.

- Low savings – If you are younger or will rely upon earning an income for years to come (and if someone is financially dependent on you), you have fewer resources to cover future expenses.

Many people will fall into one or more of these categories, which is why we think that term life insurance is a good idea for many people. Simultaneously, we rarely see situations where whole life insurance makes sense to us.

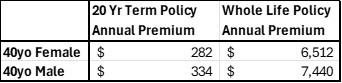

Being the number-nerds we are, we will work through examples using sample quotes from NerdWallet, that we hope will communicate our preference for term insurance.[2] We’ll focus on quotes for a 40-year, non-smoker in “excellent health” looking for a $500,000 death benefit, either as a whole life policy or a 20-year term policy.[3]

If our fictitious policy holder buys either policy on their 40th birthday, then meets their untimely demise before their 60th birthday, they’ll receive $500,000 (obviously). In that situation, the much cheaper term policy would be a clear winner in terms of its “bang for the buck.” However, a death after that 60th birthday doesn’t necessarily mean that a whole life policy is a good value.

Starting with whole life policies, the policyholder must pay annual premiums for their entire life, but since the $500,000 death benefit does not change, the longer you live, the more you pay for the policy, and the lower your “return on investment” when you eventually kick the bucket.

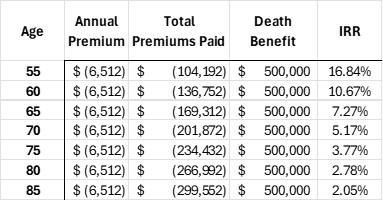

To put this into numbers, we can consider the internal rate of return (IRR) of the whole life policy based on different life expectancies. We’ll use the 40-year-old female in this example and present five-year increments starting at age 55:

To make sure we’re on the same page, the IRR is the annual rate of return that investing the annual premiums would need to earn to equal $500,000. For example, if the policyholder invested $6512 per year at a consistent 10.67% return starting at their 40th birthday, they would have $500,000 at age 60.

According to the Social Security Administration, a 40-year-old female in the United States has a life expectancy of another 41 years, or age 81.[4] Looking back at our table above, that means that the effective return on that $500,000 policy at age 81 is under 3% per year. Considering the long-term average annualized returns of 3-month US Treasury Bills (about as safe of an investment there is) is 3.36%, the 3% IRR on the full life policy looks uninspiring to us.

Now let’s consider what could happen if our imaginary 40-year-old female friend chooses the 20-year term insurance policy. If she has a strong desire to leave a death benefit or inheritance, one option is to invest the difference in cost between the whole life policy and term policy.

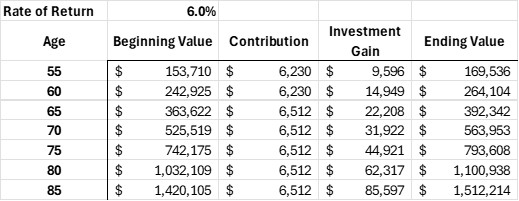

So, if our tragically still nameless hypothetical female investor purchases the 20-year term policy for $282 per year and diligently invests $6,230 per year (the difference between the whole life and term policies), we can project values for her savings using an estimated 6% return, which is a reasonable expectation for a balanced account with a healthy mix of stocks and bonds.

If our investor—Jane Doe, perhaps?—were to die before her 60th birthday, we know that the term life policy would pay her the full $500,000 death benefit in addition to the accumulated savings from the table, meaning, if she died at age 55, she would receive a total of $669,536 – still above the $500,000 from the whole life policy. Once Ms. Doe turns 60 and her term policy lapses, however, she would only receive the accumulated savings. For example, if she died at age 65, she would only have accumulated $392,342. According to the chart, her accumulated savings will recover to above $500,000 sometime just before her 70th birthday. Here is the payout comparison of the two strategies in graph form:

Looking at the graph, where the blue line is above the red line, the term policy and savings strategy is superior to a whole life policy. If Ms. Doe dies between the relatively narrow window of about age 60-69, the whole life policy makes sense, but at any other point the term policy and investment strategy would be more rewarding. If she lives to her life expectancy of 81, even though the term policy would have long since lapsed, her accumulated savings would be worth more than double the whole life policy’s $500,000 payout.

Insurance companies and their sales representatives will often try to talk up features of some policies like dividends, cash values that can be borrowed, variable policies that may be tied to stock performance (also called Universal policies), or tax-free death benefits. We would like to remind you, as the saying goes, “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” We can assure you that these features, while maybe enticing, do not come from the goodness of the corporate heart.

Fortunately, almost all these features are available to investors with a taxable brokerage account or an IRA. Many publicly traded securities (both stocks and bonds), make payments to the owners of those securities (and we have written about why we encourage indifference between dividends or stock buybacks). Brokerage accounts can provide liquidity in a variety of ways, including borrowing mechanisms. And at death, depending on the size of your estate and who the money is going to, you may not have tax considerations to worry about, and there are other strategies that can help reduce estate taxes.

If you or someone you know is evaluating whether to purchase life insurance, we are happy to be a resource and talk you through your options. We do not sell insurance or any other products that generate commissions for us, so we are on the same side of the table and our duty is to put our clients first, always.

If you have any questions about this blog, or other questions about your finances, please contact Blue River Capital Management at 503.498.9283 or at info@brcm.co.

This information is intended to be educational and is not tailored to the investment needs of any specific investor. Investing involves risk, including risk of loss. Blue River Capital Management does not offer tax or legal advice. Results are not guaranteed. Always consult with a qualified tax professional about your situation.

[1] https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/insurance/life-insurance-agent-commissions

[2] https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/insurance/term-vs-whole-life-insurance

[3] We think age 40 is close to the time that many people consider purchasing life insurance, but the actual quotes you receive can change considerably, especially for different death benefits, although we expect that the relationship between term and whole life policies are likely to be relatively consistent.

[4] https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html