Tariffs have dominated the news over the last few weeks. We are sure most of our readers have digested many articles recently on the subject, and while neither of us have PhDs in Economics[1], we hope we can provide some unique insight on them and their impacts on markets that you haven’t heard up to this point.

First off, we need to define what a tariff is. A tariff is a form of a tax on imports that is paid by the importer. So, for example, when a US manufacturer imports raw materials to be used at its manufacturing facility, it would pay a tax on those raw materials, assuming a tariff is in place for them.

Historically, tariffs have been used extensively to raise tax revenue, protect certain domestic industries, and address trade deficits. Tariff rates in the 1800s were sometimes above 40% but have consistently decreased over time to around 2% today. There exists a standard economic model for a tariff and its impacts. It looks like this:

Please contain your excitement. There are a few important effects from a tariff, according to this model:

- Prices will increase.

- Fewer goods will be consumed.

- Fewer goods will be imported and more goods will be produced domestically.

- Overall, society will be worse off (by the amount of the “deadweight loss” in the yellow triangles). Economic costs will be shouldered entirely by consumers while domestic producers will experience economic gains, and the government will raise tax revenue.

Keep in mind, this model is just that, a simplified model of reality, and there are a host of assumptions underlying its validity, many of which are often violated. That is not to say the model is useless, but it should be taken with a grain of salt.

One crucial consideration is the size and breadth of the announced tariffs and their implications economy-wide. The prior chart only considers a tariff on a single market/industry and when we expand those tariffs economy-wide, as President Trump has proposed, we argue the analysis is different. Recent movements in markets would certainly imply this to be the case.

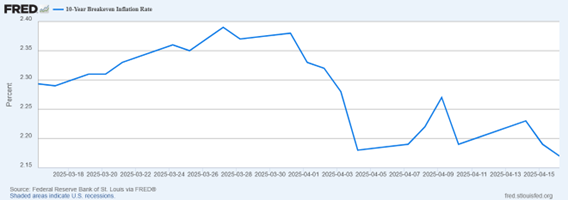

Take a look at that first tariff impact – higher prices. Certainly, higher inflation has been a talking point amongst nearly everyone with regards to these new tariffs. There’s just one problem: markets have moved in the opposite direction. Here is a chart of 10-year expected inflation over the last month. Keep in mind, President Trump announced his tariffs on April 2, approximately in the middle of this period.

Inflation expectations have dropped. What is going on here? We think there are a few reasons for this observation. The first possibility is that the expected negative impact on overall demand is outweighing the inflationary impacts of the tariffs. This is certainly possible, as individual consumers may be “tightening the belt” with regard to spending, perhaps driven by the increased level of uncertainty in the economy.

The other possibility is that the market has called Trump’s “bluff”, and it doesn’t believe he will ultimately go through with the proposed tariffs. We will not pretend to know how serious President Trump is on following through with his tariffs, but there is certainly some evidence he is willing to negotiate with individual countries.

Finally, we think the impacts of tariffs will be somewhat muted as companies try to avoid them. Firms may be able to lobby the US government for exemptions or reductions to tariffs they are exposed to, and/or they may try to bypass tariffs by shipping goods first to lower tariffed countries (think Apple chartering a plane to ship nearly-finished Chinese iPhones to Australia before forwarding them on to the US). While this strikes us as wasteful and likely to cause further drags on overall demand, most companies will look at doing everything they can to avoid these tariffs. Likely, we think all these factors are playing a role in the observed inflation expectations.

Inflation expectations are crucial to another important metric we have followed closely since the tariff announcements: interest rates. Our typical model for interest rates on US debt looks something like this:

Nominal interest rate = Real risk-free interest rate + inflation adjustment

We will spare you the algebra, but one can transform this equation using some economic identities to look like this:

Nominal interest rate = Real growth rate + inflation adjustment

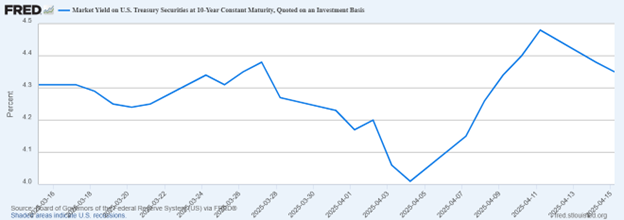

Now think about each of these variables and what has happened to them since the tariff announcements. As we have seen, inflation expectations have dropped and, if the standard economic analysis from above, media pundits, and economic analysts are to be believed at all, real growth rate expectations have also dropped. So the conclusion is that interest rates must have come down, right?

After an initial drop, the 10-year US Treasury rate (a common proxy for the US Treasury market as well as a benchmark for mortgage rates) increased fairly dramatically before settling at a slightly higher rate than pre-tariff announcements, as of this writing.

Similar to inflation expectations, the market has moved in the opposite direction than what many people claimed would happen. So what do we think is going on? Well, the above interest rate equations make an important assumption about US Treasuries – they are risk-free. In finance, the risk-free rate of return is a crucial metric that in practice we usually estimate using the US Treasury market. But in recent weeks, we think the market is pricing in some added level of risk for these securities. To put it into mathematical terms, here is the general equation we would use for risky fixed-income securities (like corporate debt, for example):

Nominal interest rate = Real growth rate + inflation adjustment + risk premium

The value of the risk premium term should be dependent upon the likelihood of the entity in question paying off its debts. Historically, the US has never defaulted on its debt, but we think the market is pricing in some probability that it may in the future, hence the implied increase in the risk premium.

We find the likelihood of the US defaulting on its debt to be low, but not zero, and our base-case scenario is that this implied risk premium will decrease over time. This does not necessarily mean interest rates will come down, as there are other variables at play, but all else equal, that would be our conclusion.

As for our client portfolios, we have not made significant changes to our asset allocations and, thus, overall portfolio risk levels have remained stable. Economic uncertainty, whether it is determining tariff impacts on inflation, overall demand, or interest rates, is extremely high. This uncertainty has clearly bled over to the financial markets where we have seen high levels of volatility. Elevated volatility is not necessarily a sign of an unhealthy market. It may make investors feel nauseous, but it does have a silver lining – it is often a precursor to positive returns.

If you have any questions about this blog, or other questions about your finances, please contact Blue River Capital Management at 503.334.0963 or at info@brcm.co.

This information is intended to be educational and is not tailored to the investment needs of any specific investor. Investing involves risk, including risk of loss. Blue River Capital Management does not offer tax or legal advice. Results are not guaranteed. Always consult with a qualified tax professional about your situation.

[1] We are not completely illiterate in Economics, Jack does have a degree in the field!